My Experience as a Scientific Diver

Armed with a compass, a reel of measuring tape and a slate; I enter Nemo Reef in Havelock, geared up and ready to dive. Beside me are my buddy — another student — and our instructor. We’re here to learn how to collect data underwater and make sense of what’s changing beneath the surface in an area that witnessed a mass bleaching event just a year ago.

Photo: Venkatesh Charloo

How I got here

I completed my PADI Open Water certification in 2015, but it’s only in recent years that I’ve begun diving more consistently and feeling truly committed to it. My journey began by wrestling with the fundamentals; buoyancy, control, comfort — just learning how to feel at home underwater. Eventually, that gave way to wonder: I started seeing the reef like a picture-perfect gallery, gliding through rays of light and shoals of fish, peeking under overhangs and admiring the life that moved around me as if I weren’t there at all.

Diving has always brought me an indescribable joy — like it couldn’t possibly get better. But that perspective shifted during an EarthCoLab Marine Ecology course in the Maldives, when I was asked to observe a single Pocillopora coral for 20 minutes at a depth of 5 metres. The more I looked, the more I saw – a whole world unfolding within this small space – I was hooked into finding out more about how this world worked. I wanted to go beyond the visuals of it, and understand the inner workings of a complex and fascinating system.

On my journey to look closer, I came across the Samudra Scientific Diver program, run by Samudra Conservation, partnering with Marine Life of Andamans, Coastal Impact, and Dive India in Havelock. Held from 22–27 June, it offered another lens through which I could understand our impact on the sea. Before I knew it, I was one of ten people in the very first batch, transitioning from recreational diving to scientific diving, learning to dive with purpose.

What is scientific diving?

Scientific diving sits at the intersection of recreation and research, empowering divers to become field scientists and ecological storytellers. The data collected can directly support researchers, communities, and policymakers in understanding how ocean systems are changing. Prajakta Kuwalekar from Marine Life of Andamans, whose brainchild this program was, felt the urgency of this work firsthand, after witnessing a mass bleaching event just last year that affected 80% of the coral in the Andamans — only to surface and realise no one was talking about it. Often this is the case: out of sight, out of mind, and this is what we are aiming to change.

Preparation

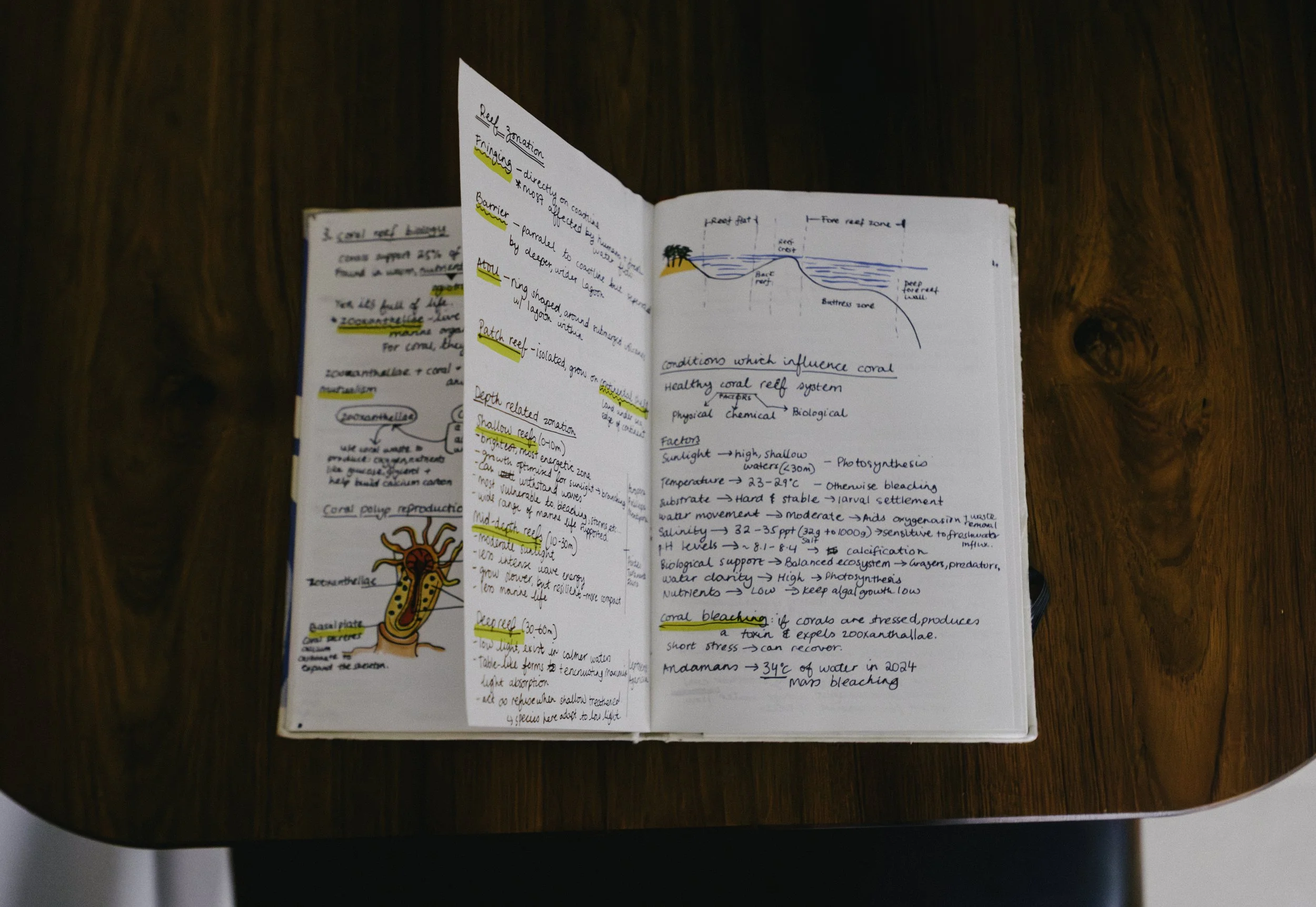

Before the program began, we were sent a comprehensive document that laid the foundation for what it means to be a scientific diver. It covered key techniques, introduced us to marine systems and coral reef biology, and included sections on buoyancy and underwater navigation. Packed with photos, videos, and additional reading materials, it’s a resource I know I’ll return to. Having this context ahead of time made everything we covered in person feel more familiar and meaningful.

My notes while reading the manual

On land

The ten of us who had gathered from various places in India came from all walks of life. We ranged in age across four decades, split evenly between women and men, each bringing a different background and story to the mix. We had amongst us, a biologist, ecologist, a commercial diver, engineers, photographers and artists. The time outside the water was spent at Dive India in focused learning sessions — covering theory, engaging in discussions, playing interactive games, and reviewing the data we collected.

Much of the teaching was led by India’s only advanced scientific diver, Jeremy Josh from Coastal Impact. He introduced us to data collection techniques and guided us through outdoor simulations to build the core underwater skills we’d need: laying transects, navigating with a compass, using quadrats, and filming with precision. Each day, we assessed the quality of our collected data and began to interpret what it might reveal.

Transects: Fixed line used to systematically study and record data in a specific area

Quadrats: A square frame used to define a fixed area

On land practice of laying down transects. Photo: Pooja Sampath

We also learned from Sagar Nambiar, a zoologist and dive instructor, who taught us how to identify fish through subtle cues — shape, tail shape, fin placement. Mrigank Save, a dive instructor and ecologist, walked us through reef mapping, how to navigate using a compass and general dive safety. One particularly memorable session was an interactive game designed by marine biology student Sarah Drego, where each of us embodied an organism within a marine ecosystem. We acted out how each organism depends on others to survive, linking ourselves to the ones we relied on. Once our web was complete, we played out what would happen if the water temperatures rose or species disappeared. It illustrated just how interconnected these systems are. All in all, a very rounded sharing of information and technique!

The discussions — both in groups and one-on-one — were enriching, exploring topics like how to create meaningful change in coastal systems without causing disruption, and how to work in collaboration with local communities. We shared stories of close-up fish encounters, reflected on how diving in the Andamans has changed over the years, and heard the personal journeys that had brought each of us to this program.

Between sessions: tidepool wanders and hangouts with the island dogs

In water

My group included Pratheeksha, my dive buddy, and our underwater instructor Venkatesh Charloo, founder of Coastal Impact and a pioneer of diving in India. We were assigned a section of Nemo’s reef marked by a floating bottle — a space we would become very familiar with.

The purpose of the survey techniques we learnt was to access benthic cover, and record reef fish communities. Both of these indicate the health of the reef. Benthic cover surveys show what the sea floor is made up of – coral, algae, rubble or sand. Understanding reef fish communities is central to monitoring the health and functionality of coral reef systems. For example, a healthy reef might show a dominance of herbivores that control algae, or high predator diversity indicating complex food webs.

Prathi and I took turns laying and reeling in the line, careful not to disturb any coral. The trick was to move slowly and deliberately. Visibility was low — which made the work more challenging, but also forced me to use tools, rather than rely on sight.

The reef map of Nemo’s reef, with our study area highlighted

Our group: Venkat and Prathi. Video: Sarah Drego

Once we got the feel for the transect setup, we practised three main techniques:

Line Intercept Transects (LIT) using video: We learnt this technique for two purposes: to record benthic cover and record the reef fish communities.

To assess benthic cover, we swam slowly — about 3 minutes over 20 metres — filming directly downward from 1 metre above the tape. Maintaining consistent height, speed, and camera angle was tough.

To record fish species, we filmed straight ahead within a 5m imaginary cube, panning only when fish appeared to the sides or above. This would then allow an expert to review and ID the fish to form their datasets.

A slow swim along a 20m transect, capturing the reef's benthic life. Photo: Venkatesh Charloo

LIT for Benthic Cover — 20m survey using video

23 June | Transect 2

LIT for Fish Survey — 20m video transect recording reef fish

June 24 | Transect 1

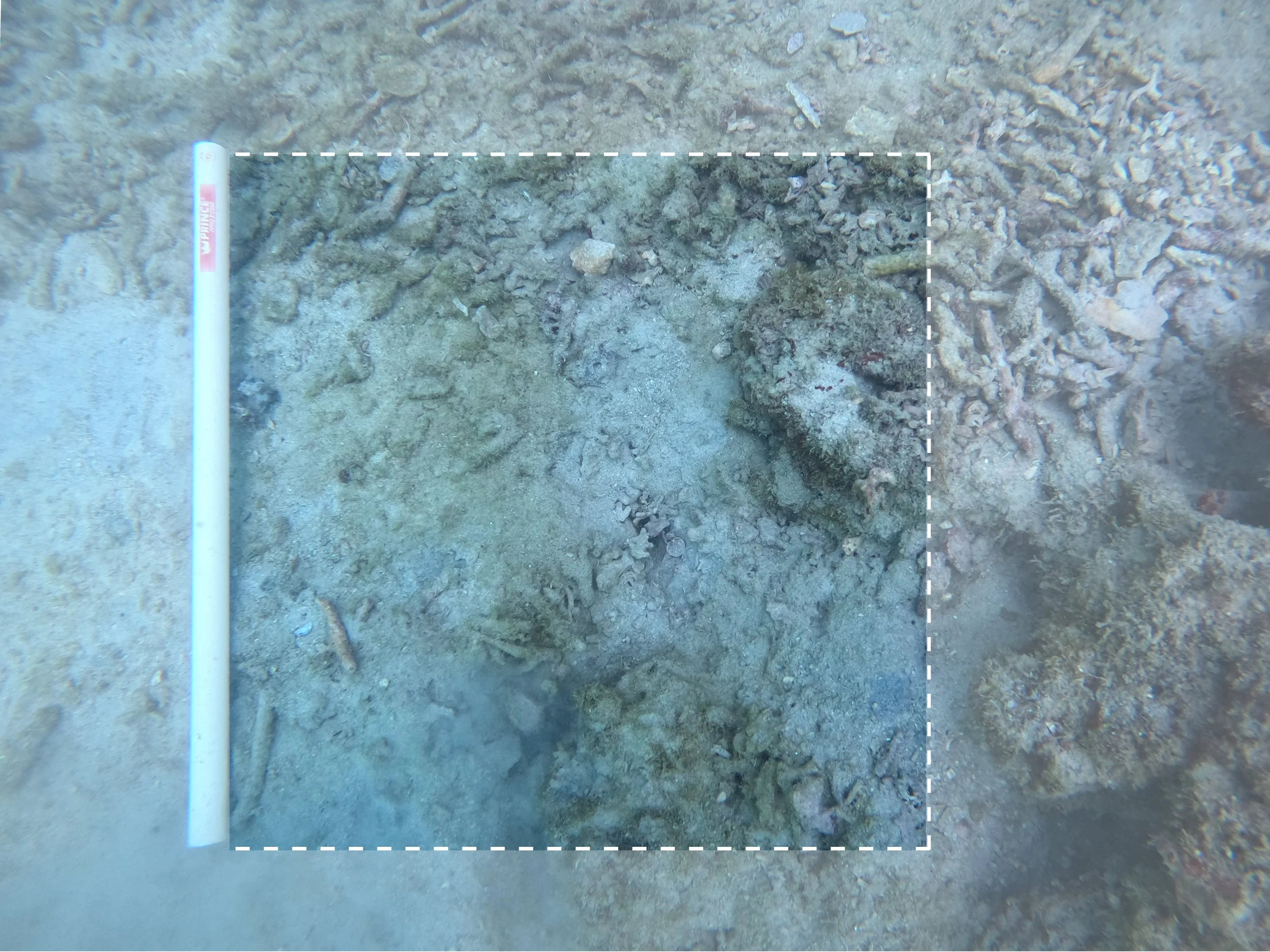

Photoquadrat Benthic Analysis: This technique also captures the composition of benthic communities using photos rather than video.

It is done by taking still images from fixed points along the transect line. Every 2 metres, we placed a pipe to mark one side of a square and had to mentally visualise the remaining sides. The photo had to be taken from directly above the imaginary square, ensuring the full area was captured without any cropping or distortion. This was especially challenging when the transect lay across coral or rock.

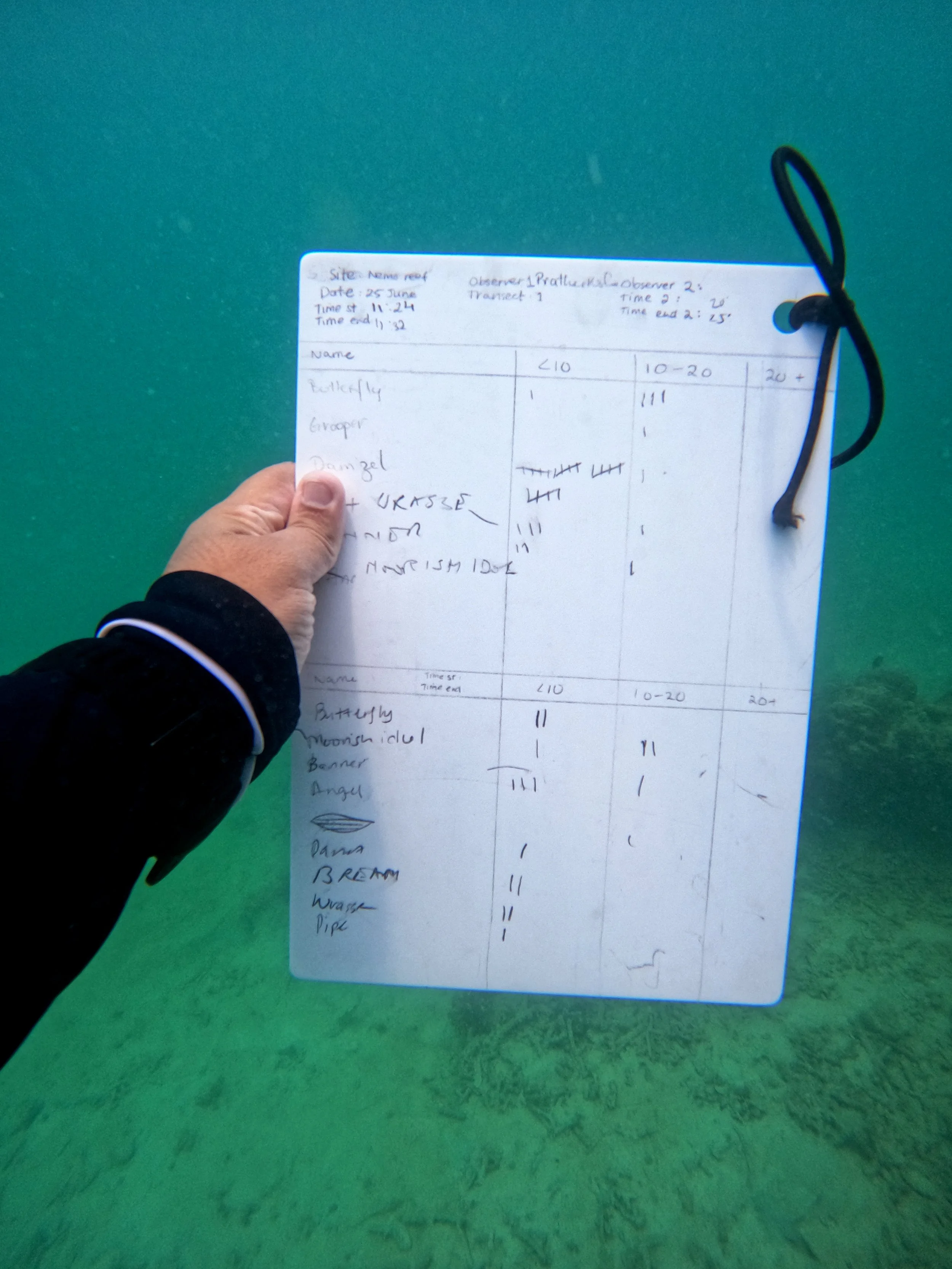

Underwater Visual Consensus of Fish (UVC): This technique is used to assess the composition, abundance, size, and diversity of reef fish communities.

A more advanced method, this technique involved identifying, sizing, and counting fish in real time, with no photo or video backup. We visualised a 5m box around us as we swam the transect and recorded everything we saw — except damselfish (which we intentionally left out, as their large numbers would require a separate survey). We prepped our slates in advance for quick note-taking, and later compiled the data on land. In real-world research, this technique is typically used only by highly experienced divers who are skilled at accurately identifying local reef fish on the spot — a level of expertise that takes years to develop.

Our slate after transect 1 (Prathi’s section above and mine below)

The group’s collated data from the Fish UVC. 25 June

The first batch

Being part of the first batch to participate in this felt like stepping into something just beginning to take shape — both exciting and a little uncertain. There were no alumni to refer to, no stories to fall back on, just a group of us figuring it out together as we went. That unfamiliarity fostered a real sense of camaraderie; we learned not just from our instructors, but from one another’s mistakes, questions, and small wins. We were lucky to be guided by a group of people who were undoubtedly experts in their fields — patient, passionate, and deeply invested in getting this off the ground. It felt special to be laying the groundwork for something bigger — to know that others would follow, and that in some small way, we were shaping the path they’d walk.

All of the participants and facilitators. Photo: Pooja Sampath

The power of storytelling

Pooja Sampath, an accomplished filmmaker and executive producer known for her socially aware storytelling, joined us to document the program. As part of her work with Ocean Culture Life, the program’s community partner, Pooja filmed throughout the week. She captured the learning, the laughter, the moments of connection with the sea and everything in between.

The output of Pooja’s work will be shared by Ocean Culture Life as part of their storytelling showcase.

Ocean Culture Life is a marine focused charity, rooted in storytelling. They harness the power of narrative to inform, engage, and mobilise individuals towards ocean conservation.

Mindset shift

This program changed the way I look at a reef. Instead of simply admiring the beauty of each creature or trying to identify what I see, I’ve started looking deeper — what does it mean, for example, to see an overpopulation of a single species? Even before entering the water, studying the location on a map gives me clues about the ecosystem I’m about to enter. It’s also helped me ask better, more informed questions — especially when speaking to locals about how the sea has changed over time, and understanding how those shifts connect to larger global patterns. It’s also changed how I think about my role as a diver and photographer — with curiosity, I also feel a responsibility to tell these stories with more depth and context.

This experience will stay with me and shape the way I dive for years to come. I’m deeply grateful for everything I learned — both within the curriculum and far beyond it — but most of all, for finding a community so deeply connected to the sea.

To the wonderful group I learned alongside, and to Coastal Impact, Marine Life of Andamans, Dive India and Ocean Culture Life — thank you.

Venkat expertly guiding me through the Fish UVC, which I found challenging! Photo: Pooja Sampath